The way we think about creativity today—as a unique and valuable human trait—has a long history that has shaped our understanding of what it means to be “creative.” The word creativity itself is derived from the Latin term creare, meaning “to make” or “to bring forth.” However, the concept has taken on very different meanings and who we consider “creative” has evolved dramatically. From the divine muses of ancient Greece to the scientific inventors of the Industrial Age, creativity has changed along with human progress and our view of art, intellect, and individuality. Here’s a journey through creativity across the ages.

1. Ancient Times: Creativity as Divine Inspiration

Greece: Divine Inspiration and the Muses

In ancient Greece, creativity was seen as a gift from the gods, channeled through the Muses—nine goddesses each governing a particular art or science. The Greeks believed that poets, musicians, and thinkers were merely conduits for divine ideas rather than creators themselves. Invoking the Muses, as seen in Homer’s Iliad and Hesiod’s Theogony, was a way to call on inspiration beyond human capacity, emphasizing that true creativity was otherworldly

The Muses’ influence was so profound that the term “museum” is derived from them, representing a place where knowledge and creativity converge.

Each Muse had a specific domain:

- Calliope – the Muse of epic poetry, often considered the foremost of the Muses. She was depicted with a writing tablet, as her role was to inspire poets to tell grand tales, such as Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey.

- Clio – the Muse of history, symbolizing the preservation of stories and events. Artists, historians, and writers who sought to document reality looked to her as a guide.

- Erato – the Muse of love poetry, inspiring poems and songs about passion and romance. She often appeared with a lyre.

- Euterpe – the Muse of music, especially wind instruments, was seen as a source of pleasure and harmony, often depicted with a flute.

- Melpomene – the Muse of tragedy, represented with a tragic mask and the club of Hercules, symbolizing the serious aspects of human experience.

- Polyhymnia – the Muse of sacred poetry and hymns, inspiring reverence and religious devotion through verse.

- Terpsichore – the Muse of dance, bringing rhythm and movement, frequently shown dancing or with a lyre.

- Thalia – the Muse of comedy, contrasting Melpomene, symbolizing joy and laughter through comic theater.

- Urania – the Muse of astronomy, associated with the heavens and often portrayed with a globe and compass, inspiring scholars to study the stars and the universe.

Rome: Practicality and Cultural Fusion

While the Romans were influenced by Greek views, they adopted a more pragmatic approach to creativity. Roman art, literature, and architecture were often inspired by Greek precedents, but they adapted these forms to suit the needs of a vast empire. Creativity was celebrated when it served practical purposes, such as enhancing public life, infrastructure, and the military.

Roman architecture reflects this functional creativity. Innovations like concrete and the arch allowed the Romans to build grand structures like the Pantheon and aqueducts, emphasizing engineering prowess and utility. For Romans, creativity wasn’t just an abstract ideal; it was a tool for asserting cultural power, creating infrastructure, and improving public life

Egypt: Creativity as Cosmic Order and Sacred Art

In Egypt, creativity was less about personal expression and more about honoring the gods and preserving cosmic order, or ma’at. Egyptian art, writing, and architecture followed strict guidelines that emphasized harmony, balance, and continuity, rather than individual style. Creativity here was viewed as a sacred act that aligned human work with divine principles.

Hieroglyphics and temple art serve as prime examples. Egyptian hieroglyphs were not just written language but an art form, with each symbol representing both sound and meaning. Artists followed established conventions in depicting gods and pharaohs, using specific proportions to reflect divinity and authority. Egyptian temples and monuments, such as the Pyramids of Giza, were designed to honor the gods and the pharaohs’ journey to the afterlife, embodying an eternal vision rather than innovation for its own sake

Curiosity Corner:

-

In ancient Greece, artists didn’t “sign” their works as we do today. Artisans were anonymous, as their role was seen more as skilled labor rather than personal expression. It wasn’t until the Renaissance that individual recognition for creative work became common. But we’ll talk about this later.

-

The Romans were masters of concrete. They invented a blend with volcanic ash that made their structures incredibly durable. The Pantheon’s dome, still standing today, is the world’s largest unreinforced concrete dome—a marvel nearly 2,000 years later

- The Egyptian Book of the Dead, illustrated with hieroglyphic texts and scenes, was created to guide the deceased through the afterlife. These creations were considered powerful enough to aid souls in their journey, showcasing creativity as a spiritual service.

2. Creativity in the Middle Ages

During the Middle Ages (5th to 15th centuries), creativity continued to be viewed as an extension of the divine, yet each culture had its own perspective.

Christianity and the Role of Divine Inspiration

In Christian Europe, creativity was perceived as a divine blessing rather than a human trait. Art, literature, and architecture were seen as expressions of faith rather than individual creativity.

The Gothic cathedrals exemplify this: builders and sculptors remained anonymous, as their works were seen as dedicated to God rather than to personal acclaim. The construction of cathedrals like Notre-Dame de Paris and Chartres Cathedral exemplified medieval creativity. These structures were designed to inspire awe and direct attention toward the heavens. Builders utilized flying buttresses and stained glass to create dramatic interiors, where light symbolized divine presence.

Art often served as a “visual Bible,” meant to educate a largely illiterate population on religious stories and values.

The Islamic Golden Age: Creativity as Knowledge and Invention

In the Islamic world, the Golden Age of Islam (8th to 14th centuries) was marked by a flourishing of knowledge, art, and scientific inquiry. Creativity was often expressed through calligraphy, geometric patterns, architecture, and advancements in science and philosophy. Islamic artists avoided depicting human figures in religious contexts, focusing instead on abstract forms and patterns, which were seen as expressions of the infinite nature of God.

Chinese and Japanese Perspectives: Creativity as Harmony and Craftsmanship

In China and Japan, creativity was closely tied to harmony with nature, craftsmanship, and tradition. For example, Chinese landscape painting aimed to capture the spiritual essence of nature rather than precise realism, reflecting Daoist and Confucian values of balance and contemplation. Japanese Zen gardens and calligraphy emphasized simplicity, discipline, and attention to detail as means of connecting with a larger, harmonious whole.

In each of these cultures, creativity wasn’t viewed as a secular or solely human trait; it was either a spiritual act or a craft that reflected one’s dedication to the divine, natural order, or ancestral wisdom.

Curiosity Corner:

-

Illuminated Manuscripts: Monks and nuns meticulously hand-copied and illustrated books, particularly the Bible. These illuminated manuscripts were adorned with intricate designs and vibrant colors, which were believed to honor the divine word. Some took years, even decades, to complete, and errors were seen as potential signs of the devil’s influence.

-

Al-Jazari’s Automata: The 12th-century inventor Ismail al-Jazari designed early programmable machines, including clocks and intricate water-powered automata. His creative engineering greatly influenced later designs and foreshadowed aspects of modern robotics.

- The Tale of Genji: Written by Japanese noblewoman Murasaki Shikibu in the early 11th century, it’s considered the world’s first novel. Creativity in literature was valued in Japan, but authors like Murasaki were expected to be discreet, often publishing anonymously or pseudonymously.

3. Creativity in the Renaissance: Individual Genius and Innovation

Moving from the Middle Ages to the Renaissance (14th to 17th centuries), creativity took on a new, transformative role. In Europe, the Renaissance marked a “rebirth” of classical knowledge and values, drawing from Greek and Roman ideals while emphasizing individual achievement, intellectual curiosity, and innovation. This period celebrated the concept of the “Renaissance man”—a person skilled in multiple disciplines—embodied by figures like Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo, who were seen as both artists and scientists.

Creativity as Personal Genius

During the Renaissance, artists, writers, and thinkers began to be recognized as unique individuals with extraordinary abilities, a shift from the collective or anonymous creativity of the Middle Ages. The term “genius” was used to describe figures who could channel divine inspiration in innovative ways, and creativity was perceived as a highly personal talent that could bridge art, science, and invention.

Leonardo da Vinci: Known for works like The Last Supper and Mona Lisa, Leonardo exemplified the Renaissance ideal of blending art and science. His notebooks, filled with anatomical sketches, engineering designs, and studies of nature, illustrate a view of creativity that merged observation with imagination, turning human curiosity into groundbreaking art and innovation.

For me, Da Vinci’s history and sketches have been a profound influence, sparking my own desire to sketch and explore ideas from an early age. His endless curiosity resonates with my own creative journey. Inspired by his ability to combine practical engineering with artistic vision, I strive to bring a similar depth to my work, balancing structure with the freedom to experiment.

Michelangelo: Michelangelo’s creative process was described as “liberating” his sculptures from the marble. Works like David and the Sistine Chapel ceiling reflected a new belief that the artist’s personal vision could transform raw materials into something transcendent, celebrating both human potential and divine inspiration

.

Patronage and the Flourishing of the Arts

Creativity during the Renaissance was also driven by the support of wealthy patrons, such as the Medici family in Florence. These patrons funded artists, scientists, and philosophers, encouraging experimentation and the pursuit of beauty. This backing allowed artists more freedom to explore themes outside of strict religious contexts, incorporating mythological, humanist, and secular themes that expanded the scope of creative expression.

The Printing Press: Creativity as Knowledge Sharing

A significant catalyst for creativity in the Renaissance was the printing press, invented by Johannes Gutenberg around 1440. This revolutionary technology enabled mass production of books, making knowledge accessible to a broader audience than ever before. Artists and thinkers could now share their ideas widely, leading to an explosion of creativity as new concepts, literature, and artistic techniques spread rapidly across Europe.

Curiosity Corner:

-

Humanism: Renaissance humanism emphasized the study of classical texts, which promoted the value of individual potential. This intellectual movement encouraged people to question established authority and explore the arts, philosophy, and sciences independently.

-

Gutenberg Bible: One of the first major books printed using movable type, the Gutenberg Bible democratized access to religious texts and paved the way for a more literate and informed society. This marked a shift toward creativity as a shared experience, where ideas could inspire innovation far beyond individual workshops or cities

4. Creativity in the Enlightenment: Rationality and Original Thought

The Enlightenment (17th to 18th centuries) built upon Renaissance ideas, but with a focus on reason, science, and intellectual freedom. Creativity was no longer just about artistic expression; it became a tool for exploring human potential, scientific discovery, and societal progress.

Creativity as Intellectual Exploration

Enlightenment thinkers like Isaac Newton and Voltaire pursued creativity in science and philosophy, questioning traditional beliefs and embracing rationality. Creativity was associated with skepticism and originality, often challenging religious or political authority in favor of individual reasoning and empirical evidence. This shift emphasized that creativity wasn’t mystical but rather a disciplined approach to understanding and innovating in the world.

Isaac Newton: Newton’s theories on gravity and motion illustrate Enlightenment creativity as grounded in experimentation, mathematics, and observation rather than divine inspiration. His creative process involved questioning established knowledge, leading to groundbreaking advancements in physics.

Can you believe it was his insight that the same force pulling an apple to the ground also kept the moon in orbit? That revelation, that gravity extends into space, gave us a fundamental understanding of the universe and laid the foundation for modern physics.

Voltaire and Rousseau: Writers like Voltaire used creativity to critique society, questioning authority and advocating for political reform. Their works fueled democratic ideals and inspired later revolutions by reimagining governance and individual rights.

The Rise of Individualism

Enlightenment ideas helped to solidify creativity as an individual pursuit of knowledge and personal expression. This period celebrated the notion that each person could contribute unique insights to society, laying the groundwork for modern concepts of originality, intellectual property, and innovation.

Did you know?

- The Encyclopédie: Edited by Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d’Alembert, this comprehensive work gathered knowledge across disciplines, embodying Enlightenment values of education, accessibility, and the sharing of creative ideas.

5. Creativity in the Romantic Era: Emotion, Nature, and the Sublime

Following the Enlightenment, the Romantic era (late 18th to early 19th centuries) reacted against the rationality of the Enlightenment by focusing on emotion, nature, and individual experience. In this period, creativity was seen as a deeply personal, often mystical force that could connect individuals to the natural world and to profound, sometimes turbulent emotions.

Creativity as a Connection to Nature

Romantic artists, poets, and musicians saw nature as an immense source of inspiration, representing freedom, beauty, and raw, untamed power. They believed creativity allowed individuals to forge a spiritual connection with the natural world, experiencing what they called the “sublime”—a mixture of awe, wonder, and sometimes fear.

William Wordsworth: One of the foremost Romantic poets, Wordsworth wrote about his deep, almost spiritual connection to nature. In poems like “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud,” he celebrated the inspiration he found in the natural landscape, portraying it as a profound creative force.

Creativity as Emotional Depth and Individual Expression

For the Romantics, creativity was intensely personal and emotional, driven by passion, introspection, and, sometimes, melancholy. Romantic artists often delved into themes of love, loss, and longing, viewing creativity as an exploration of the inner self.

Ludwig van Beethoven: Beethoven’s music reflects this Romantic ideal, filled with powerful contrasts, emotional depth, and expressions of triumph and tragedy. His compositions, such as his Symphony No. 5 and Moonlight Sonata, captured a range of intense feelings, moving audiences with their passion.

The Artist as Visionary and Outsider

Romanticism also emphasized the idea of the artist as a misunderstood genius, someone driven by intense emotion and imagination who might not conform to societal norms. Creativity, to the Romantics, was often a solitary, introspective journey that set artists apart as visionaries.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: Shelley’s novel reflects Romantic themes of the sublime, with its descriptions of wild landscapes and the moral dilemmas surrounding scientific exploration. The novel’s main character, Victor Frankenstein, embodies the dangers and isolation of unchecked creative ambition.

Creativity and the Supernatural

Romantics often explored themes beyond the physical world, including the supernatural and mysterious. They saw creativity as a means of accessing otherworldly realms and understanding the mysteries of life and death. This fascination with the supernatural can be seen in the poetry of Lord Byron and in the works of Gothic writers like Edgar Allan Poe.

The Romantic Era presents creativity as deeply personal, emotionally charged, and even mystical, positioning the artist as both a visionary and a conduit for the sublime forces of nature and emotion. This era paved the way for modern ideas about creativity as a unique, transformative experience that connects the creator to both the world and their inner self.

Curiosity Corner:

-

Beethoven continued to compose even as he lost his hearing, viewing his creative work as essential to his identity and as a way to channel his inner experiences into music.

-

Frankenstein was inspired by a competition among friends to write the best ghost story. Shelley’s work went on to become one of the most enduring novels of the Romantic period, blending creativity with themes of science, horror, and the supernatural.

- The Gothic Novel: Romanticism gave rise to the Gothic genre, with novels like Dracula by Bram Stoker and The Castle of Otranto by Horace Walpole blending supernatural elements with creative storytelling to evoke fear and wonder.

6. Creativity in the Industrial Age: Innovation and Practicality

As the Industrial Revolution took hold in the late 18th and early 19th centuries, creativity was increasingly tied to innovation and technological advancement. This era saw creativity moving from personal expression and emotional depth, characteristic of Romanticism, to a more utilitarian form. In the face of rapid urbanization, technological growth, and changes in work environments, creativity became synonymous with inventiveness, problem-solving, and efficiency.

Creativity as Mechanization and Invention

Inventions like the steam engine, the spinning jenny, and later, the telegraph transformed society, accelerating production and communication. Creators of the time were not just artists but engineers, scientists, and inventors. Figures such as James Watt, who refined the steam engine, and Samuel Morse, who developed Morse code, used creativity to push technological boundaries, which reshaped industries and everyday life.

The Rise of Industrial Design and Applied Creativity

As machines began producing goods on a massive scale, the need for design in products grew. This gave rise to industrial design, a field where creativity was applied to improve both the aesthetics and functionality of manufactured products. Figures like Josiah Wedgwood, an English potter, pioneered mass production techniques while incorporating artistic design, combining creativity with the efficiency demanded by the market. He is sometimes referred to as the “Father of English Potters” and was a key figure in developing consumer ceramics. His creative innovations, like the development of “creamware” and use of factory-based production, helped make fine pottery accessible to the middle class.

Creativity in Art: Realism and the Artist as Social Commentator

The shift toward industrialization brought a reaction in the art world, where Realism emerged as a response to Romantic ideals. Artists like Gustave Courbet and Honoré Daumier began portraying ordinary working-class life, addressing the harsh realities of industrial society and exploring themes of social justice. Creativity became a way to document, critique, and make sense of a world that was rapidly changing.

Courbet’s The Stone Breakers is a powerful example of Realism, depicting two laborers engaged in backbreaking work. Courbet’s choice to paint such a gritty scene was revolutionary, as art had traditionally focused on idealized landscapes and historical subjects.

Creativity in Literature: The Rise of Science Fiction

As technology advanced, literature began to explore new themes that were directly influenced by industrial developments. Science fiction emerged as a genre that reflected both excitement and anxiety about the potential of science and industry. Writers like Mary Shelley, H.G. Wells, and Jules Verne used creativity to imagine the future, explore the implications of technology, and question ethical boundaries.

Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein: Though written earlier in 1818, Frankenstein captures the Industrial Age’s tension between progress and ethical responsibility. Victor Frankenstein’s creation of life mirrors society’s ability to harness nature, raising questions about the consequences of scientific ambition.

Jules Verne: Often called the “father of science fiction,” Verne’s novels, such as Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea and Around the World in Eighty Days, were inspired by the technological advancements of his time. Verne’s work popularized the concept of “futuristic creativity,” imagining inventions and adventures far beyond the known world. His visions of submarines, air travel, and space exploration were strikingly prescient. His works inspired real-world inventors and remain iconic examples of how creativity in literature can predict and influence future technological advancements

7. Creativity in the 20th Century

Continuing our journey into the Modern Era and 20th Century, we witness creativity blossoming alongside rapid technological advances, significant social upheavals, and shifting cultural landscapes. This era brought creativity into new domains, from abstract art and digital design to environmental movements and space exploration. Here’s a look at how creativity evolved and adapted during this time:

Creativity in the Early 20th Century: The Avant-Garde and Innovation

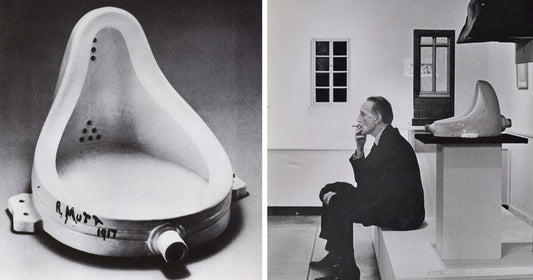

The early 20th century saw art and literature breaking away from traditional forms, ushering in avant-garde movements like Cubism, Surrealism, Futurism, and Dadaism. These movements challenged established norms, aiming to express the subconscious, distort reality, and explore fragmented perspectives. Artists like Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí experimented with form, color, and symbolism, reflecting a new era that valued creative exploration over realism.

Curious Fact:

-

Dadaism began as a response to the horrors of World War I, rejecting conventional art in favor of absurdity and spontaneity. Artists like Marcel Duchamp used “found objects,” like a urinal he titled Fountain, challenging the very definition of art

Scientific and Technological Creativity: The early 20th century was also marked by monumental scientific breakthroughs. Albert Einstein’s theory of relativity, developed in 1905, reshaped physics and opened up new ways of understanding time and space, which influenced art and literature. Similarly, Sigmund Freud’s work on psychoanalysis inspired writers, artists, and filmmakers to delve into the subconscious, making creativity a tool for exploring hidden layers of the human mind.

Mid-20th Century: Creativity as a Tool for Social Commentary and Revolution

By the mid-20th century, creativity was increasingly used as a means of social and political commentary. With world wars, civil rights movements, and shifting cultural dynamics, artists, writers, and musicians used their work to question authority, protest injustice, and promote change.

The Beat Generation: In the U.S., writers like Jack Kerouac and Allen Ginsberg rejected mainstream values in favor of a more personal and spontaneous style of writing. Their works, often filled with introspection and criticism of societal norms, were influential in the countercultural movements of the 1960s.

Abstract Expressionism: In the visual arts, Abstract Expressionism, led by figures like Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, rejected structured forms in favor of emotional expression. This movement reflected a post-war world that felt fractured and unstable, valuing personal experience and individualism over traditional structure

The 1960s and ’70s saw the rise of “happenings”—spontaneous, interactive art performances designed to break down barriers between artist and audience. These events were meant to make viewers part of the creative process, challenging the idea of passive spectatorship

.

Late 20th Century: Digital Revolution and Globalization

In the late 20th century, the digital revolution transformed creativity across all fields. With the invention of computers, the internet, and digital art software, creativity became more accessible, interactive, and collaborative.

Digital Art and Design: Tools like Adobe Photoshop (launched in 1988) revolutionized visual art and design, allowing artists to create and manipulate images in unprecedented ways. 3D modeling software opened up new possibilities in fields like animation, architecture, and gaming, reshaping how we think about art and creativity in the digital age.

In fact, computers opened up a whole new world for me when I began creating video games in high school. The fact that I didn’t need physical tools or materials to bring my ideas to life felt like stepping through a portal into limitless possibilities. I could design characters, build environments, and develop levels—all from my computer screen. It was both fascinating and captivating, allowing me to explore digital art with Photoshop, experiment with 3D modeling, and even try my hand at composing music for my games. This experience gave me a first taste of merging creativity with technology, a blend that continues to shape my work today.

And how has technology influenced the way you create? Or if you are not using it yet, do you think you could benefit from specific software or digital products that will make your workflow better and maybe open new doors for your craft?

Music and Film: Advances in technology also revolutionized the music and film industries. Synthesizers, electronic music, and sampling allowed for new sounds and genres, while CGI (computer-generated imagery) transformed filmmaking, giving rise to blockbuster movies that could blend reality with digital fantasy, like Jurassic Park and The Matrix.

Street Art: With graffiti and street art, artists took to public spaces, using creativity as a voice for communities often overlooked by mainstream art. Artists like Jean-Michel Basquiat and Banksy used the streets as their canvas, making art more democratic and accessible

8. Creativity Today and Beyond: Innovation, Sustainability, and Collaboration

Moving into the 21st century, creativity is now a multifaceted concept spanning art, science, technology, and social impact. Today’s creative landscape is increasingly collaborative, with digital platforms allowing global teams to innovate together in real-time. Creativity is also more interdisciplinary, as fields like bio-art, sustainable design, and AI-driven innovation blend science and art in unprecedented ways.

Sustainable Creativity: With a growing focus on environmental impact, modern creativity often seeks to balance beauty and functionality with sustainability. From eco-friendly architecture to upcycled fashion, creative fields are adapting to address global challenges.

AI and Machine Learning: Artificial intelligence has entered the creative realm, from generating art to composing music. While AI prompts discussions about originality, it also opens up new opportunities for collaboration, with AI becoming both a creative partner and a tool for generating fresh ideas.

I’ve also used AI extensively in my work, including the very research you’re reading now on the history and evolution of creativity.

Beyond that, AI played a crucial role when I was building my CNC router (I used PrintNC plans, just Google it if you are interested). It became my assistant, helping me navigate wiring, power management, software settings, and troubleshooting countless issues. Whether in research or practical tasks, AI has proven to be a valuable partner in my process.

Crowdsourced Creativity: Platforms like Kickstarter and Patreon allow creators to fund projects through audience support, giving power to individual creators and enabling more diverse, community-driven projects.

9. Conclusion: Creativity as Humanity’s Evolving Legacy

The journey of creativity from ancient times to today reveals an ever-evolving concept shaped by human needs, cultural shifts, and technological progress. Where creativity was once attributed to divine forces, it’s now a democratic and inclusive force that drives innovation and fosters community. As we move forward, creativity will likely continue to adapt, addressing challenges that future generations have yet to imagine.

Looking back at creativity’s journey, I’m reminded that the true beauty of making lies not in the perfect result but in the willingness to start and make. Each era has shown that creativity adapts, expanding as tools evolve and as people find new ways to express themselves. Today, creativity is in reach for anyone who wants to try, and the journey begins not with mastery but with a simple act of making.

In my next article, I’ll share more of my personal experiences - what creativity means to me and how the practice of making continues to shape who I am.

10. Creativity for Everyone: The New Era of Making

Today, unlike in the past, each and every one of us has access to create - to imagine something in our minds and bring it into the world, whether onto a screen or into our hands. If you think you’re not creative or that imagination isn’t your strength, it’s likely just because you haven’t started yet or believe it’s “not your thing.”

Creativity is more accessible now than ever. Affordable machines like laser cutters and 3D printers put the power of making directly into our hands. Stores, both local and online, offer every material we could need. And with platforms like YouTube and Google, we can learn any skill we set our minds to. Whether it’s building wooden stick planes, working with clay, or drawing characters, we can start making things with just a bit of time and dedication.

I was lucky to start young, surrounded by creative people and encouragement. For me, creativity felt like destiny. But there are countless ways to get into making - I know fellow creators who didn’t pick up a pen or a tool until their 20s and are now professionals. I truly believe that anyone with the desire can access this incredible process, even if it takes time and effort to develop.

So, where do I start?

It’s easy to get caught up in wanting to make only “cool” things or to doubt the worth of an idea before it even starts. Even now, I catch myself judging ideas too soon, dismissing thoughts that don’t feel “good enough.” Yet, some of my best work has come from ideas I almost abandoned or from random mistakes. You never know where the gold lies until it reveals itself. Every creative attempt, whether a triumph or a lesson, adds value and is worth the effort.

So go ahead—start with things that may feel “stupid” or small - it’s totally fine! No one creates something great on the first try. Look up a tutorial on YouTube, find something that sparks your interest, and give it a go. Then try something different, and then something else. Imagine that whatever you make might end up in the trash later. For me, this mindset frees me from pressure, allowing me to enjoy the process. And one day, I know I’ll create something I’m truly proud of. This is how my journey began, and it’s still how it goes today.

7 comments

https://www.acerthailnd.com/

https://www.acerthailnd.com/huaythai

https://www.acerthailnd.com/contact

https://github.com/turingaicloud/quickstart/issues/10

https://github.com/kvspb/nginx-auth-ldap/issues/259

https://github.com/Kr1s77/FgSurfing/issues/2

https://github.com/stawel/ht301_hacklib/issues/17

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219483

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219515

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219516

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219517

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219522

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219527

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219528

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219529

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219530

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219531

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219532

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219534

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219537

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219539

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219540

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219544

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219545

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219546

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219547

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219548

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219549

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219550

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219551

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219560

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219561

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219562

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219574

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219580

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219583

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219585

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219486

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219484

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219490

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219496

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219491

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219492

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219495

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219494

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219497

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219498

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219499

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219493

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219500

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219501

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219502

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219503

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219504

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219505

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219506

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219507

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219519

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219518

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219520

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219523

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219526

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219524

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219525

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219521

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219536

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219555

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219576

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219579

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219556

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219558

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219557

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219559

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219564

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219565

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219566

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219570

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219568

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219575

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219577

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219582

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219581

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219567

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219578

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219571

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219569

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219589

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219593

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219595

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219619

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219620

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219621

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219622

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219623

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219624

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219625

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219626

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219627

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219628

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219629

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219630

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219631

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219632

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219633

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219634

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219635

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219637

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219638

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219639

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219640

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219641

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219642

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219645

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219659

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219660

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219666

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219667

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219668

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219669

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219670

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219604

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219605

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219606

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219610

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219608

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219607

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219612

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219609

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219611

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219613

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219614

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219618

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219616

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219617

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219615

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219654

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219651

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219653

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219650

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219657

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219658

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219652

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219655

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219663

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219665

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219662

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219661

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219649

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219664

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219656

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219646

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219644

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219647

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219671

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219672

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219673

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219674

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219675

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219676

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219677

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219678

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219679

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219680

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219681

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219682

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219683

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219684

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219685

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219686

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219687

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219688

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219689

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219690

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219691

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219692

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219693

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219694

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219695

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219696

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219697

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219698

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219699

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219700

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219701

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219702

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219709

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219710

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219711

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219712

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219713

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219714

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219715

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219716

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219717

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219718

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219719

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219720

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219721

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219722

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219723

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219724

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219725

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219726

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219727

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219729

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219730

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219731

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219740

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219741

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219742

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219743

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219750

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219751

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219752

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219753

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219703

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219705

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219707

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219708

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219706

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219732

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219704

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219733

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219734

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219735

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219737

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219739

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219738

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219736

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219744

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219745

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219748

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219746

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219749

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219747

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219761

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219763

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219762

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219760

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219756

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219755

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219754

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219758

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219757

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219759

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219765

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219766

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219767

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219768

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219769

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219770

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219771

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219772

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219773

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219774

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219775

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219776

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219777

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219778

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219779

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219780

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219781

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219782

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219783

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219784

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219785

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219786

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219787

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219788

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219789

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219790

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219791

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219792

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219793

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219794

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219795

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219796

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219797

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219806

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219807

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219808

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219809

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219810

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219811

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219812

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219813

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219814

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219815

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219816

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219817

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219818

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219819

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219820

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219822

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219823

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219824

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219825

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219826

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219878

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219880

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219881

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219885

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219886

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219890

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219891

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219892

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219893

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219894

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219803

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219800

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219801

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219802

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219828

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219827

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219805

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219834

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219833

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219829

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219804

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219831

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219839

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219842

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219836

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219832

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219837

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219838

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219841

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219835

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219843

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219845

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219844

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219847

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219846

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219848

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219830

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219849

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219850

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219851

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219852

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219853

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219854

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219855

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219856

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219857

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219858

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219859

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219860

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219861

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219862

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219863

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219864

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219865

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219866

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219867

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219868

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219869

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219870

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219871

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219872

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219873

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219874

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219875

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219876

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219877

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219879

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219882

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219883

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219884

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219887

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219888

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219889

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219896

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219897

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219898

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219899

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219900

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219901

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219902

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219903

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219904

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219905

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219906

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219907

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219908

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219909

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219910

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219911

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219912

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219913

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219914

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219915

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219916

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219917

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219918

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219919

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219920

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219921

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219922

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219923

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219924

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219925

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219926

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219927

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219934

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219928

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219930

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219932

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219929

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219941

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219938

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219940

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219950

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219945

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219942

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219937

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219935

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219931

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219936

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219933

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219948

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219947

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219949

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219939

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219944

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219946

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219943

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219955

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219954

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219953

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219952

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219993

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219958

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219960

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219961

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219962

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219963

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219965

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219968

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219969

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219970

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219971

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219972

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219973

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219974

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219975

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219976

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219977

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219978

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219979

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219980

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219981

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219982

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219983

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219985

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219986

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219987

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219988

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219989

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219990

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219991

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219992

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220000

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220001

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220002

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220003

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220004

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220005

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220006

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220007

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220008

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220009

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220010

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220011

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220012

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220013

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220014

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220015

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220016

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220017

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220018

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220019

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220080

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220081

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220082

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220083

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220084

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220085

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220086

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220087

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220088

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220089

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219994

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219995

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219997

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219996

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220022

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219998

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220021

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220020

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220023

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220024

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220025

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220026

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220027

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220028

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220029

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220030

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220031

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220032

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220033

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220034

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220035

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220036

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220037

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220038

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220039

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220040

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220041

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220042

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220043

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220044

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220048

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220051

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220049

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220052

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220050

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220054

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220055

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220060

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220056

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220065

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220057

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220078

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220066

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220053

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220068

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220059

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220069

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220077

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220062

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220071

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220063

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220072

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220064

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220076

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220073

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220067

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220074

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220070

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220075

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220079

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220102

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220106

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220107

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220108

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220109

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220110

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220111

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220112

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220113

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220114

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220092

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220094

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220097

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220098

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220099

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220100

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220101

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220096

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220103

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220104

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220048

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220050

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/220051

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219882

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219852

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219853

https://sistacafe.com/summaries/preview/219856

https://www.readawrite.com/a/98daef69f8e29be4e41605c2c9a62c2b

https://www.readawrite.com/a/8efddb48243391e719153a8c549d1f56

https://www.readawrite.com/a/6a1ecf276db5ae5ce023a1f46061d209

https://www.readawrite.com/a/f3ebcc921b2d723e76076155dee60c11

https://www.readawrite.com/a/4159a0f386e527b85670136912a8104f

https://www.readawrite.com/a/30972df3c8bb679f2dcc74f43445195f

https://www.readawrite.com/a/f290608acdddf792e4c29385db6b9154

https://www.readawrite.com/a/f1e3410841babfa25c3d5fe720283195

https://www.readawrite.com/a/d0497f18d2b558c6fc4541b15e81ee4a

https://www.readawrite.com/a/c8a33281a5a1ac6726d6a390d7ab5327

https://www.readawrite.com/a/57509a190a774f17b3e2d05f4e57abed

https://www.readawrite.com/a/2cfb4b82853e0ee6f2036b1c16eac0e1

https://www.readawrite.com/a/f968817c5963f1176389978fe301b027

https://www.readawrite.com/a/a55ef62192c50800b209a29b7cfd8119

https://www.readawrite.com/a/59f023855f12efceba8617bb9eabd4a9

https://www.readawrite.com/a/983769f53fbe82f2d456823f5ef0b816

https://www.readawrite.com/a/4bde3f64395c50c712af6f06ca4eff36

https://www.readawrite.com/a/ab3d0efe648b908e632da3740dea3581

https://www.readawrite.com/a/41367b34654f6f8cd51db158edf6fbc5

https://www.readawrite.com/a/3bba04c5de0c3603bb23699473070123

https://www.readawrite.com/a/cf5cd4f9f04a10b176109da4bc60b191

https://laylo.com/laylo-mcrsfpl/eXodIbh8

https://laylo.com/laylo-aveacdq/V44hucnu

https://laylo.com/laylo-b8gyoxb/f3mF6t3n

https://laylo.com/laylo-hqaljwf/IaaGjl32

https://laylo.com/laylo-agh9th0/EaQPZzAl

https://laylo.com/laylo-bohg6js/IUDbzDoM

https://laylo.com/laylo-vkoobrk/CKmAReJk

https://laylo.com/laylo-5l2wkrm/sJsrZIIe

https://laylo.com/laylo-pdtwoyi/gCnYnHye

https://laylo.com/laylo-wj2httn/fP11GFdH

https://laylo.com/laylo-dd2jlvi/pWt2oFRh

https://laylo.com/laylo-zrzmu5r/9KfK1rqb

https://laylo.com/laylo-xlhpojy/WcqKrrEk

https://laylo.com/laylo-mjua1ua/gQSmja9Y

https://laylo.com/laylo-kxdaiye/nG0BTww3

https://laylo.com/laylo-5pewzmo/fNvSVtns

https://laylo.com/laylo-fxja5b9/3GYJJmHk

https://laylo.com/laylo-gsn1jpy/3zWiUqay

https://laylo.com/laylo-txzsajm/c8aw7FEI

https://laylo.com/laylo-rwixilg/m97cocXu

https://laylo.com/laylo-s1dvbjy/z5kK1N6N

https://laylo.com/laylo-cbitamk/YfyTa4k0

https://laylo.com/laylo-ztzn6ae/Uf9EFIwT

https://laylo.com/laylo-kvbmwxa/xmS7DGkf

https://laylo.com/laylo-axxnwor/3zqwpCDC

https://laylo.com/laylo-qkkfeo1/u8jC8kgX

https://laylo.com/laylo-vdt3i2e/QDM87tQc

https://laylo.com/laylo-u3aotk5/r8Dc8C9b

https://laylo.com/laylo-n3rrfwp/8keTr148

https://laylo.com/laylo-vnxnv9k/F9XZPGCD

https://laylo.com/laylo-droxuqb/v62KHKpa

https://laylo.com/laylo-j7efaw6/rCZ2kUjZ

https://laylo.com/laylo-xmis9bn/vZ2qtsE0

https://laylo.com/laylo-pj84sqj/Hrnpo3Ni

https://laylo.com/laylo-pyynebq/lQXaofD1

https://laylo.com/laylo-allzmkv/kL9Vh1cc

https://laylo.com/laylo-allzmkv/kYsyzJdb

https://laylo.com/laylo-allzmkv/UUz4VXFO

https://laylo.com/laylo-allzmkv/Q7XRHibn

https://laylo.com/laylo-9pt7n87/eM91EHJu

https://laylo.com/laylo-9pt7n87/8S7cr4mX

https://laylo.com/laylo-9pt7n87/C5LCSTp4

https://laylo.com/laylo-9pt7n87/DdktasXz

https://laylo.com/laylo-lzczuj3/CKpN5lkB

https://laylo.com/laylo-lzczuj3/mRR7SM0L

https://laylo.com/laylo-lzczuj3/RhbOaCDm

https://laylo.com/laylo-9pt7n87/c1EfdtIK

https://laylo.com/laylo-9pt7n87/hMOWqGEf

https://laylo.com/laylo-9pt7n87/WCTHq0h4

https://laylo.com/laylo-xu4xfge/lOdBq7JL

https://laylo.com/laylo-xu4xfge/bvouDNhz

https://laylo.com/laylo-xu4xfge/Mw1I58vU

https://laylo.com/laylo-ven748x/pmz94337

https://laylo.com/laylo-ven748x/bzt2k1cU

https://laylo.com/laylo-ven748x/VbyS2Mne

https://laylo.com/laylo-ven748x/3BMqvsDD

https://laylo.com/laylo-zpthte9/mHevk9bX

https://laylo.com/laylo-zpthte9/tZcqgiw8

https://laylo.com/laylo-zpthte9/YyREQgTt

https://laylo.com/laylo-zpthte9/RWlYcrWu

https://laylo.com/laylo-iun1wgq/RBqMZ87M

https://laylo.com/laylo-iun1wgq/7oQEoHQt

https://laylo.com/laylo-iun1wgq/I99YCQ79

https://laylo.com/laylo-iun1wgq/iu344OMm

https://laylo.com/laylo-iun1wgq/WKLeqZ6n

https://laylo.com/laylo-pzuvkep/hHAoyjqb

https://laylo.com/laylo-pzuvkep/chAzia35

https://laylo.com/laylo-pzuvkep/ouyLNJsN

https://laylo.com/laylo-pzuvkep/zgJPxJbd

https://laylo.com/laylo-pzuvkep/nz5BWypb

https://laylo.com/laylo-ec9ihej/oMhYPnNT

https://laylo.com/laylo-ec9ihej/pHXeElFh

https://laylo.com/laylo-ec9ihej/El5edAjG

https://laylo.com/laylo-ec9ihej/rOZOJIVZ

https://laylo.com/laylo-ec9ihej/o0jPjCbg

https://laylo.com/laylo-azj1i8q/OMnl9aI7

https://laylo.com/laylo-azj1i8q/cQtdn7Rm

https://laylo.com/laylo-azj1i8q/BkkokSuy

https://laylo.com/laylo-azj1i8q/vSrckRg8

https://laylo.com/laylo-azj1i8q/RtLSPyS6

https://laylo.com/laylo-1lepwzt/t0Yg5tuP

https://laylo.com/laylo-ohiflqv/ITwGJPfq

https://laylo.com/laylo-hrnjg1m/vlGofcxL

https://laylo.com/laylo-qpzuuvz/ogbfs7NR

https://laylo.com/laylo-pmuwhts/VFQrBBGG

https://laylo.com/laylo-rmajsvz/nBxTrZYV

https://laylo.com/laylo-mr3ggdw/ACDshRfW

https://laylo.com/laylo-em8zo21/5Cms9YTw

https://laylo.com/laylo-dzgoqnr/J4jCCTHs

https://laylo.com/laylo-r6zrcwm/xLv3Ds5f

https://laylo.com/laylo-ekl9lwn/1BAdzkx8

https://laylo.com/laylo-hdvfhx6/7TA56Otx

https://laylo.com/laylo-qemtvpz/hCpTQJEC

https://laylo.com/laylo-ugglfiu/arO770EO

https://laylo.com/laylo-yutxaxq/f0NnOxMX

https://laylo.com/laylo-kngugmd/wMFDOxcc

https://laylo.com/laylo-yplgt5j/GBFCFTt0

https://laylo.com/laylo-irqnbfc/qkbjKriE

https://laylo.com/laylo-tzn2fxa/gchOYQ0E

https://laylo.com/laylo-lqwtzsu/MLBjfTtX

https://laylo.com/laylo-ud629kw/mP8GdUG5

https://laylo.com/laylo-rc7mk4o/jVDeesOy

https://laylo.com/laylo-vpybkax/m80JCGj3

https://laylo.com/laylo-h0xppme/tbGNzVZs

https://laylo.com/laylo-yxuw4x3/750E9loL

https://laylo.com/laylo-vlu6jce/CX5lC0m3

https://laylo.com/laylo-tjyufrn/i0ZhVhnM

https://laylo.com/laylo-5o0o7lc/QEeEgJZX

https://laylo.com/laylo-dfgbo9f/CPCuGqE8

https://laylo.com/laylo-69nrgtz/AxyQmWOo

https://laylo.com/laylo-dk1tycl/qomkYxnz

https://laylo.com/laylo-fshhjvt/B7bCHKpU

https://laylo.com/laylo-4lccwsp/agLo1oHq

https://laylo.com/laylo-dbzcwwx/fX753b9p

https://laylo.com/laylo-l4ukbky/rwUdsopR

https://laylo.com/laylo-4wqdazx/mIajbTSV

https://laylo.com/laylo-b42db9i/Mr82W2be

https://laylo.com/laylo-si7crb3/6f86Jqqh

https://laylo.com/laylo-fshhjvt/HhctXMxP

https://laylo.com/laylo-fnw7mlo/wFbWJpY7

https://laylo.com/laylo-f9hvl17/CgeLtE68

https://laylo.com/laylo-apu79ti/WCz46SJN

https://laylo.com/laylo-5xfolxo/XDyAnHiJ

https://laylo.com/laylo-mkp8k1a/rMbx3xoN

https://laylo.com/laylo-0hdch72/1kH5pwkm

https://laylo.com/laylo-uljqzmu/NYl5jfGj

https://laylo.com/laylo-3a172v2/pqctWS66

https://laylo.com/laylo-72q9osc/5JbHIqm4

https://laylo.com/laylo-rf5wunr/E1jx9hai

https://laylo.com/laylo-54gt5hu/uoGLfZs3

https://laylo.com/laylo-49ylq77/trQIcrJM

https://laylo.com/laylo-dlsog6f/r8bK0yw6

https://laylo.com/laylo-8jsfhk9/UAznnTmY

https://laylo.com/laylo-99zprcv/RxFpIHeh

https://laylo.com/laylo-rzo6bmp/SCkxbN9G

https://laylo.com/laylo-l4axgvy/VBsKMC4w

https://laylo.com/laylo-luy5fs6/Qt8fM4UW

https://laylo.com/laylo-xqt9xvj/otWs8ekw

https://laylo.com/laylo-btwb0sh/G4TetqLM

https://laylo.com/laylo-49wtrxb/obqO5oCe

https://laylo.com/laylo-oaok3s4/eSCOVwEC

https://laylo.com/laylo-bwakvtt/XupcEQ87

https://laylo.com/laylo-odgslrn/tskRqt9T

https://laylo.com/laylo-qsymosj/SLYA1sqQ

https://laylo.com/laylo-vbybkty/zw0A72wf

https://laylo.com/laylo-lt0iptd/EzYObala

https://laylo.com/laylo-wrkbq6k/XZdnra27

https://laylo.com/laylo-wtjs7wl/SDSsqwvc

https://laylo.com/laylo-x6l4vhb/IPTWJAyz

https://laylo.com/laylo-wwzxyp7/oAnHwTqd

https://laylo.com/laylo-6kiw78x/nGbRVXCS

https://laylo.com/laylo-9hsmqxh/Z1THZe9n

https://laylo.com/laylo-huhftfs/0hxboqph

https://laylo.com/laylo-1sgy04k/Tg08mA5v

https://laylo.com/laylo-lvr8rri/Jduwn0MY

https://laylo.com/laylo-gtsn2cf/bMxH1lZd

https://laylo.com/laylo-764wbw3/ISv3MgDk

https://laylo.com/laylo-8twd6t1/LYtqU79t

https://laylo.com/laylo-2gfyz3o/dAUib2mX

https://laylo.com/laylo-jbzok3a/do1riwgP

https://laylo.com/laylo-bmidket/rhY0PwCO

https://laylo.com/laylo-gadt9a9/t5NPHDwf

https://laylo.com/laylo-7axyyit/nlet0SpY

https://laylo.com/laylo-i2nqvwn/HVwIcDZt

https://laylo.com/laylo-ttaymqy/faUNsjfs

https://laylo.com/laylo-wah1brq/MTa2JZ1M

https://laylo.com/laylo-5wl0czv/oESq2xnu

https://laylo.com/laylo-den5ddc/JpoVXbs7

https://laylo.com/laylo-h9ogogp/PqNjMQLw

https://laylo.com/laylo-d6gn5ip/iHAP0MET

https://laylo.com/laylo-wcgrlxq/LnaJTv08

https://laylo.com/laylo-ywzprsw/DV1b4w5U

https://laylo.com/laylo-hjfzer3/eXeie4Ax

https://laylo.com/laylo-ljtfixo/oEdiCaoK

https://laylo.com/laylo-nauvkf6/B70imnMf

https://laylo.com/laylo-piueopc/3qLOcxVe

https://laylo.com/laylo-3aldotp/wm9XrpBG

https://laylo.com/laylo-vwz5olb/lf2B8Rk4

https://laylo.com/laylo-tn7jws5/3oHcaYr1

https://laylo.com/laylo-cpnscgn/Vy1HS9V9

https://laylo.com/laylo-hfyeaqj/peTtcdJ7

https://laylo.com/laylo-lvlnjjl/74Quc5p5

https://laylo.com/laylo-6cxttt4/gd8hLarr

https://laylo.com/laylo-u7rq55r/YjAS7nIV

https://laylo.com/laylo-vbayno4/rrYXSR0p

https://laylo.com/laylo-gnsyrrf/Q2z2LnVw

https://laylo.com/laylo-auswqju/Dovp7oUL

https://laylo.com/laylo-i92sed8/7VpEW2bf

https://laylo.com/laylo-4fjdilf/UUBUEKLs

https://laylo.com/laylo-s1np2kw/NIBeVnXQ

https://laylo.com/laylo-cpaxmbb/aJHdrVhD

https://laylo.com/laylo-flrjx7n/iJTqsZDM

https://laylo.com/laylo-wnpy8ee/BNM7MtxQ

https://laylo.com/laylo-vfzxyn5/0F4Knfcv

https://laylo.com/laylo-yf9t7xl/SJ7HYMLG

https://laylo.com/laylo-df4oskf/MJriUV7X

https://laylo.com/laylo-gjdrpgr/yfCSSweu

https://laylo.com/laylo-azkucdd/1vM34QRg

https://laylo.com/laylo-mazphwg/QnTsdpNc

https://laylo.com/laylo-2tybazd/q01ulqt6

https://laylo.com/laylo-7itph7r/nhmpzZap

https://laylo.com/laylo-7itph7r/LsWytkrE

https://laylo.com/laylo-7itph7r/OggJX8Bu

https://laylo.com/laylo-7itph7r/O1XZQbiE

https://laylo.com/laylo-7itph7r/b6eDHzUb

https://laylo.com/laylo-spbyhth/FW42Uc4y

https://laylo.com/laylo-spbyhth/JbDUhovM

https://laylo.com/laylo-spbyhth/JtrGK1en

https://laylo.com/laylo-spbyhth/yOsJpDrE

https://laylo.com/laylo-spbyhth/aYo0ERwf

https://laylo.com/laylo-9ntelby/5H1H1oFG

https://laylo.com/laylo-9ntelby/CoJ1q0uq

https://laylo.com/laylo-9ntelby/ViKtXNy3

https://laylo.com/laylo-9ntelby/g8YZEuDH

https://laylo.com/laylo-9ntelby/OfGCarPm

https://laylo.com/laylo-i9ij2oi/TcaQcTKP

https://laylo.com/laylo-i9ij2oi/AwX2ylD8

https://laylo.com/laylo-i9ij2oi/XIFrYBbD

https://laylo.com/laylo-i9ij2oi/AhG3uou4

https://laylo.com/laylo-i9ij2oi/VnkU6dWH

https://laylo.com/laylo-ufzhzcv/6sqt6kIA

https://laylo.com/laylo-ufzhzcv/QWy1bSSd

https://laylo.com/laylo-ufzhzcv/UTD5e43e

https://laylo.com/laylo-ufzhzcv/rcn6FOEo

https://laylo.com/laylo-ufzhzcv/laaYHeMt

https://laylo.com/laylo-mo0ggiy/NPTTnRu4

https://laylo.com/laylo-mo0ggiy/1JmiLkWw

https://laylo.com/laylo-0zetz06/RyuM9r3f

https://laylo.com/laylo-0zetz06/Mk0YBWRB

https://laylo.com/laylo-0zetz06/nHkIyXet

https://laylo.com/laylo-0zetz06/tQS9hoT1

https://laylo.com/laylo-0zetz06/zs3PSDiM

https://laylo.com/laylo-mo0ggiy/IVvPlEVQ

https://laylo.com/laylo-mo0ggiy/ldMPkz5J

https://laylo.com/laylo-mo0ggiy/Ghizfx7A

https://laylo.com/laylo-omps4cy/8yWhSw2h

https://laylo.com/laylo-omps4cy/MoRRQh37

https://laylo.com/laylo-omps4cy/Xe7xX7yT

https://laylo.com/laylo-omps4cy/xgZrUzbu

https://laylo.com/laylo-omps4cy/gwUWZEzV

https://laylo.com/laylo-qxbldrl/zEJKJhEK

https://laylo.com/laylo-cwmbdwu/xS6xwh39

https://laylo.com/laylo-qrryk1p/QINTMgeN

https://laylo.com/laylo-147mu4n/fMNL8wUn

https://laylo.com/laylo-db0wwgp/6JtcYVq6

https://laylo.com/laylo-wkhzwnu/VFNXO5YN

https://laylo.com/laylo-9z0i2et/8qz6cbLx

https://laylo.com/laylo-wef6zb9/kXiL8pnp

https://laylo.com/laylo-bj2ey7u/KFmVpZo9

https://laylo.com/laylo-jlfccyx/6WVqv07W

https://laylo.com/laylo-x6l4vhb/9ymbb1Iz

https://laylo.com/laylo-wwzxyp7/eYCvw13S

https://laylo.com/laylo-6kiw78x/RdpXSeLF

https://laylo.com/laylo-9hsmqxh/gcN1aRI5

https://laylo.com/laylo-huhftfs/K73nsJUf

https://laylo.com/laylo-1sgy04k/D59uxJFa

https://laylo.com/laylo-lvr8rri/F290oeo9

https://laylo.com/laylo-2gfyz3o/hZTWuNY0

https://laylo.com/laylo-gtsn2cf/acmOofZ9

https://laylo.com/laylo-764wbw3/64zsIfjf

https://laylo.com/laylo-jbzok3a/ir1U76LH

https://laylo.com/laylo-8twd6t1/5×8k3wEz

https://laylo.com/laylo-8jsfhk9/g1J28tbM

https://laylo.com/laylo-99zprcv/xJ9p1Tuk

https://laylo.com/laylo-rzo6bmp/z6urM1dP

https://laylo.com/laylo-l4axgvy/2fkP925I

https://laylo.com/laylo-luy5fs6/hghQC5CJ

https://laylo.com/laylo-xqt9xvj/Eib8HawY

https://laylo.com/laylo-btwb0sh/88zvoSBV

https://laylo.com/laylo-49wtrxb/9p8JSN2O

https://laylo.com/laylo-wtjs7wl/C9RscMUs

https://laylo.com/laylo-wrkbq6k/yimhPTms

https://laylo.com/laylo-lt0iptd/PcrZtzys

https://laylo.com/laylo-vbybkty/PAe4WOdw

https://laylo.com/laylo-qsymosj/pj6mSFBJ

https://laylo.com/laylo-odgslrn/BVbVhlmY

https://laylo.com/laylo-bwakvtt/3NUMfenO

https://laylo.com/laylo-oaok3s4/CMPgqQRg

https://laylo.com/laylo-ffxqkbe/DijMxq7l

https://laylo.com/laylo-ri4oatr/HAsQEddj

https://laylo.com/laylo-fnw7mlo/YrgyGIXF

https://laylo.com/laylo-h0xppme/PuZN4c9q

https://laylo.com/laylo-tjyufrn/fIXVEuAR

https://laylo.com/laylo-b42db9i/YBiqTuWN

https://laylo.com/laylo-vlu6jce/7LEBnAZF

https://laylo.com/laylo-yxuw4x3/jLY0TUKx

https://laylo.com/laylo-5o0o7lc/ipy5aGHz

https://laylo.com/laylo-dfgbo9f/i0KjP6De

https://laylo.com/laylo-4lccwsp/wrf5Gt2F

https://laylo.com/laylo-yutxaxq/BKqAowxq

https://laylo.com/laylo-kngugmd/jlL6R4gV

https://laylo.com/laylo-vpybkax/7fJUQLuy

https://laylo.com/laylo-ugglfiu/C29VNfEv

https://laylo.com/laylo-yplgt5j/GbizjJNC

https://laylo.com/laylo-ud629kw/elEFZiKy

https://laylo.com/laylo-irqnbfc/fpH3G8Oj

https://laylo.com/laylo-lqwtzsu/QnPNglcZ

https://laylo.com/laylo-tzn2fxa/nX9wjdAa

https://laylo.com/laylo-dk1tycl/PLdMFOj6

https://laylo.com/laylo-fshhjvt/w9R0sczH

https://laylo.com/laylo-si7crb3/bR4ivjfL

https://laylo.com/laylo-69nrgtz/ov5Rv79G

https://laylo.com/laylo-dbzcwwx/t0MRtcIv

https://laylo.com/laylo-fshhjvt/l8WwYPvF

https://laylo.com/laylo-4wqdazx/Dy1kWEIO

https://laylo.com/laylo-l4ukbky/aU8ucqlg

https://laylo.com/laylo-rc7mk4o/jVDeesOy

https://laylo.com/laylo-qemtvpz/Y85Ljyt7

https://laylo.com/laylo-ohiflqv/92y9phUr

https://laylo.com/laylo-1lepwzt/WwsPYtqH

https://laylo.com/laylo-em8zo21/kgRZCl6D

https://laylo.com/laylo-hrnjg1m/G2oNbxll

https://laylo.com/laylo-mr3ggdw/D3gyr8M9

https://laylo.com/laylo-rmajsvz/TxRx9pwq

https://laylo.com/laylo-pmuwhts/q9UtbToq

https://laylo.com/laylo-dzgoqnr/UnhMCxxN

https://laylo.com/laylo-r6zrcwm/0cXkCx7r

https://laylo.com/laylo-ekl9lwn/p2bWHXmL